INTRODUCTION

In the past two decades, there has been increasing recognition that events, treatments, emotional factors, and outcomes during pregnancy and birth can cause psychological birth trauma (PBT). PBT varies and includes aspects of real or perceived actual or threatened morbidity or mortality, as well as feelings of fear, helplessness, loss of control, and dignity.1 Emergencies and unexpected outcomes may have a negative psychological impact on birthing people as well as impacting their relationship with their newborn.2–5 These negative impacts include: the effect on their relationship with their partner or infant, including cessation of breastfeeding before they planned, social isolation, self-image, tokophobia, and desire for future children.6 The term ‘traumatic birth experience’ is used to represent the experience of interactions and/or events associated with childbirth that cause the birthing person overwhelming distress.7 For this paper, PBT will include ‘traumatic birth experiences’ as defined by the participant. An Australian study found PBT has been found to occur in as many as 45% of births,8,9 PBT experiences can lead to significant psychological impacts, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which comprises symptom clusters including re-experiencing, avoidance, negative impact on mood and cognition.6,7–10 PTSD occurs in anywhere from 4% of people postpartum to as high as 18.5% for high-risk groups.10

PBT experiences are recognized as having negative impacts on recovery and parenting, including bonding with their new infants.2–5 Long-term effects of PTSD, including lower breastfeeding levels and hyperarousal which may negatively affect relationships with others including their newborn, following a PBT, have been documented in the literature.4,5 Risk factors for PBT include induction of labour, assisted vaginal delivery (vacuum or forceps), postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), and a history of depression.11

The impact of PBT not only affects the immediate postpartum period of adjustment but also relationships with partners, connection with their infant, and desire for future children.2-5,12-16 Significant symptoms such as reliving the event, intrusive thoughts, heightened anxiety, and fear are characteristic of PTSD.17 PTSD following childbirth has only been officially recognized by the American Psychiatric Association, since 1994.18 As of 2013, it is recognized that PTSD may result from PBT, and it has been argued that childbirth-related PTSD should be considered its own disorder.17–19 The development of the City Birth Trauma Scale has provided an accessible way for clinicians and researchers to examine PTSD symptoms in birthing people and their partners.20 PBT is identified as a public health concern because of the negative impacts on the family, highlighting the importance of appropriate training for HCPs.6

Prenatal education has been widely recognized as important to the preparation process for pregnant people since the 1950s.21–26 A common part of the pregnancy experience is that prenatal education classes are provided through publicly funded and privately paid options.27,28 Antenatal education classes have been linked to a decrease in PTSD symptoms, due to a reduction in the anticipatory fear and improving the birthing person’s self-efficacy.12

The impact of prenatal education, as provided by the healthcare provider (HCP), and how that affects PBT, has not been examined before. Primary research was undertaken to attempt to determine what, if any, effect the education and information provided to pregnant people prenatally or perinatally, by HCPs, has on the trauma experienced by birthing people.

It is impossible to eliminate all obstetrical emergencies which can cause PBT. However, reducing the psychological impact of these crises while recognizing non-obstetrical emergency causes of trauma and working to reduce those, will result in improved outcomes for birthing people and their infants.

As prenatal education teaching and information sharing is entrenched in standards for Ontario Midwives, it is interesting to consider how or if it influences trauma integration. The information and education provided by HCPs in Ontario varies based on profession due to time constraints, personal and professional opinions, and expectations. While general prenatal education has been studied since first implemented in the 1950s, prenatal education provided by the HCP and the impact on PBT has not been examined.

Recommending an app or website, providing handouts, encouraging participation in a formal childbirth class, or verbal information are all methods of providing education.6,29–31 Research has identified the need for primary HCPs to gain additional skills and knowledge in trauma-informed care (TIC) and awareness of the impact of TB experiences on individuals, to reduce the propagation of trauma-inducing experiences.32 Additionally, education on emotionally focused approaches has been suggested to improve competencies with counselling skills and improve interactions with patients and colleagues.32 Midwives are in a prime position to provide TIC, and TIC education needs to be included in the curriculum of midwifery student education and ongoing professional education.33

The purpose of this research is not to assign blame but rather to articulate and draw attention to the experiences of birthing people, to learn from their narrative, to provide primary HCPs insight into individual experiences, and to provide this insight in an informed and responsive manner.

OBJECTIVES

Primary research was undertaken to address the gap in knowledge by looking at the effect of prenatal or perinatal education, as provided by healthcare providers, on the PBT experienced by birthing people. Three aims of the project were: (1) To determine any effect, either positive or negative, of information provided by healthcare providers prenatally or during the birthing experience. (2) Identify if the education and information provided to patients vary between Obstetricians (OBs), Family Medicine Obstetricians (FMOBs), and Registered Midwives (RMs) and review the impact on their patients/clients. (3) Learn from patients what HCPs can do to support and best prepare them and ideally reduce TB experiences.

METHODS

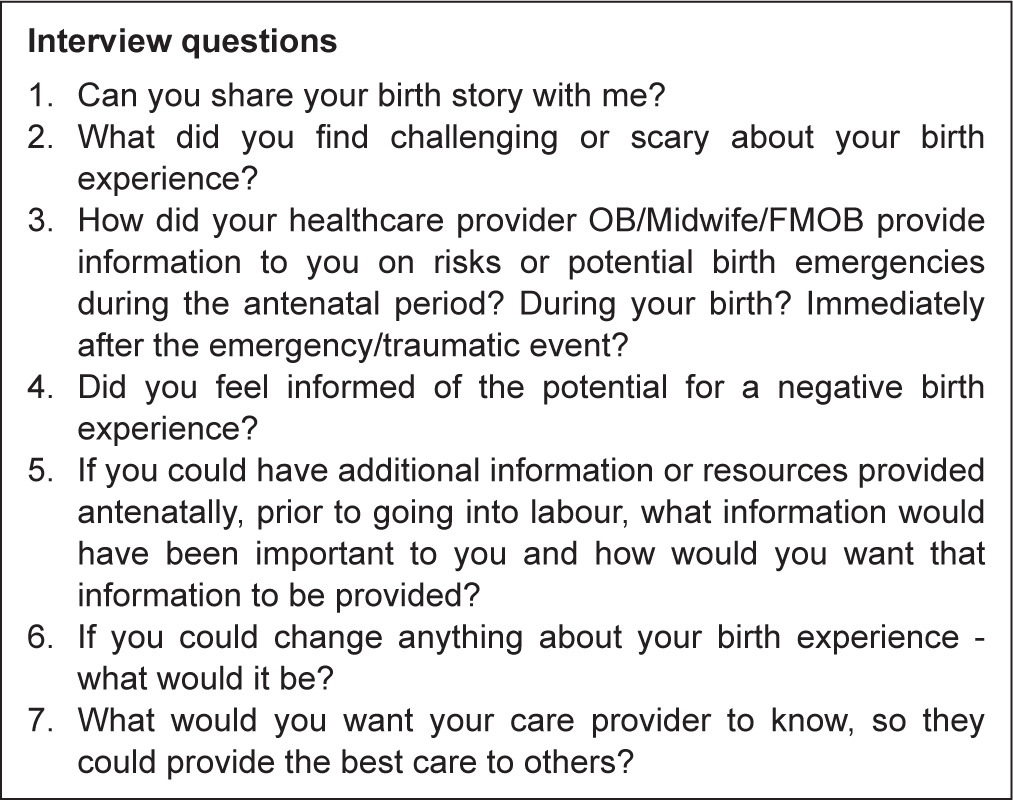

Data was collected through in-person or virtual semi-structured interviews based on participants’ preferences. Seven questions were used to elicit the participants’ opinions of the education received from their HCP and what aspects they found beneficial. Grounded theory (GT) was selected as the methodological framework, due to the gap in knowledge and the need to understand the impact of participants’ lived experiences. Adhering to the core principles of memoing and constant comparative analysis, as described by Glaser and Strauss, data was collected and rigorously analyzed through the constant comparative analysis method.34 Theory developed from the data collected, in keeping with GT’s distinct approach.35

While the benefit of formal prenatal education classes has been studied the formal and information education and information sharing by HCPs has not been examined. As a result, we need to go to the beginning and understand the impact of this type of perinatal education. The impact of this methodology allows the participants to lead the findings, and it can be responsive so that topics or ideas can be reflected on and analyzed throughout the research process. The findings provide the basis for the theory, themes, and areas of importance identified.

Data analysis began with a thorough verification of the accuracy of the transcribed interview. Each transcript was then examined line by line to identify significant comments and ideas noted. Based on the initial review, a code guide was created as the transcripts were examined. This initial coding was followed by axial coding, in which connections were made. The data was continuously compared against new data to refine and elaborate the emerging themes. Through the rigorous application of GT, key themes were identified which clarified the participants’ individual experiences, revealing strengths and areas of improvement for the practices of HCPs. The themes were reviewed with two participants for member checking. Participation was open throughout the study period; the target number of participants was achieved for each HCP type except FMOB. Interview questions are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Interview questions.

SAMPLE SELECTION

Criteria for participation included having given birth within the previous 5 years and not less than 6 months before the interview date. Participants were required to be 18 years of age or older at the time of the interview. Individuals recruited had antenatal and labour care provided by either: (1) an OB (2) an RM (3) an FMOB or (4) prenatal care by an RM which required transfer of care to an OB before 37 weeks gestation. All participants gave birth at the same tertiary centre in Southern Ontario, or they/their infant were admitted within 24 hours post-delivery to this centre.

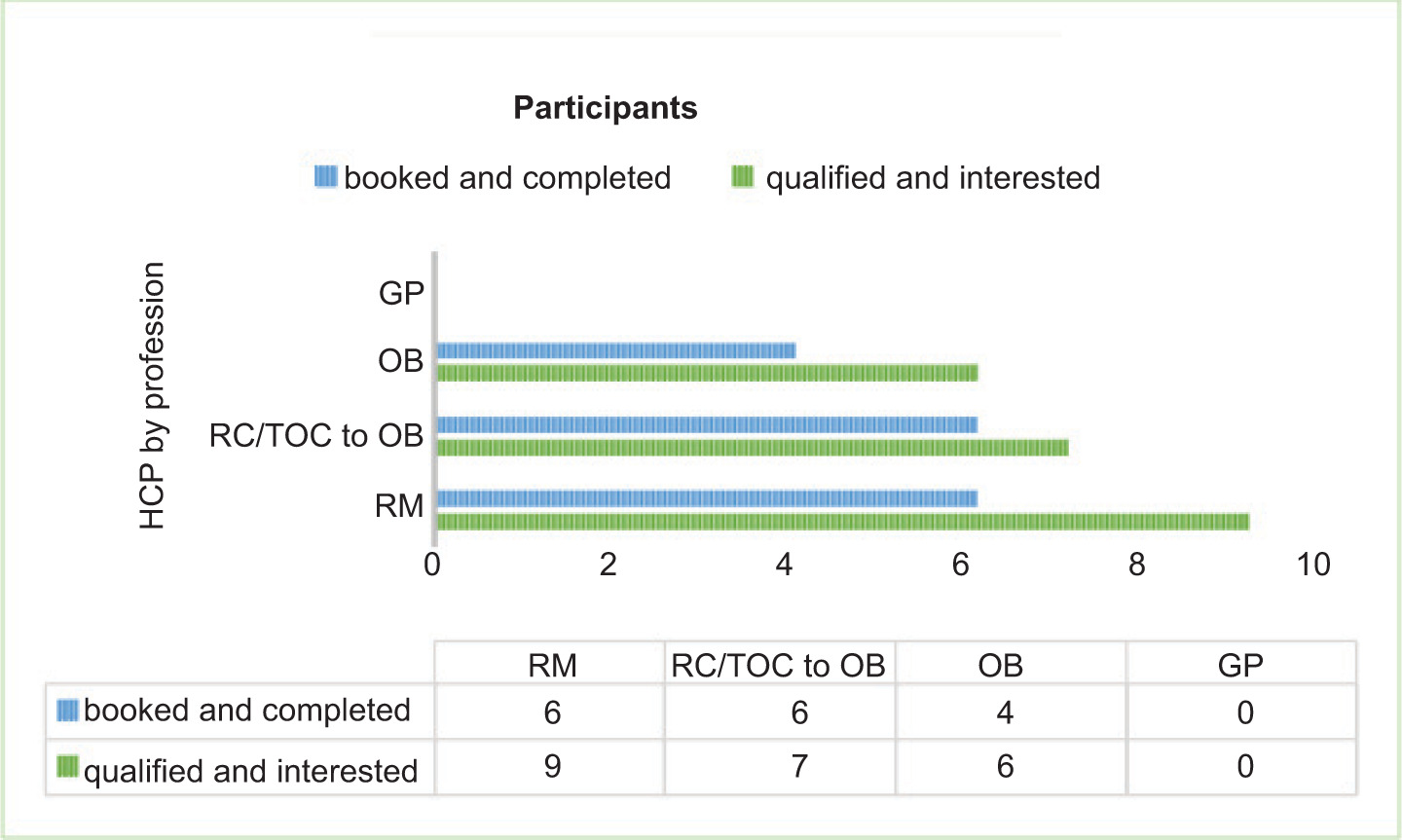

Participants were recruited between May 12 and July 15, 2023. Interviews were completed between May 17 and July 10, 2023. All participants had given birth at a tertiary centre in Southern Ontario. The participants self-identified as having a traumatic birth experience. Recruitment was completed through social media (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Participants.

RESULTS

It was humbling to receive the email inquiries regarding participation in the study, with 12 inquiries occurring within 12 hours of the initial posts on social media. A total of 36 interested individuals emailed SR (the author and primary investigator), a copy of the project information and consent documentation was forwarded via email. A total of 18 individuals were interested in participating, two were excluded as SR was their HCP at the time of their labour admission and this was felt to be a conflict of interest. Interviews with the remaining 16 interested individuals were completed. Primary research conducted found that all participants identified the information and education they received from their prenatal HCP as beneficial to their birthing experience and felt well prepared by their HCP for anticipated complications. Interviews were completed in person or virtually at the preference of the participant. Three interviews were completed in person and the remainder were completed virtually. Demographics of the participants were not compiled through the interviews; all participants disclosed their birth history, and all participants had between one and three births. Three of the participants had two PTB experiences during the inclusion period. While their experience was documented only once, prior birth experiences negatively affected the way they approached their next birth, and they shared perspectives on both birth experiences.

Patients of OBs commented that no information on normal birth or assisted birth was provided by their HCP or anyone else within the clinic. Clients of RMs reported feeling well prepared for normal labour and birth; as a result, they expected to have a spontaneous vaginal delivery and felt ready for labour. Feeling prepared for normal labour and birth was identified as reassuring. Many participants felt well cared for during their pregnancy, trusted their HCP, and looked forward to welcoming their infant.

Participants expressed that they were eager to share their story. Some shared their experiences through tears brought by memories or visceral physical reactions (such as shaking and chills) that surprised them. At the beginning of the interview with each participant the option for withdrawal at any time before July 15, 2023, was reviewed, and participants stated they had a clear understanding of their ability and the process for revoking their consent and ending their interview or removal of their interview data from consideration for analysis. Interviews were conducted at the participant’s pace and if the conversation seemed particularly sensitive participants were reminded, they did not need to answer the question. All participants received a follow-up email with the name and contact information for a Registered Social Worker specializing in birth trauma counselling, who had agreed to make herself available to any participants who needed support. This ensured that any participants who found the interview distressing had access to professional care. The interviews were conducted to gather information as long as the information gathered did not cause harm to the participants and was not solely for the benefit of the researcher. Throughout the interviews, many participants shared that speaking about their experience was helpful and important to them, these statements led directly to the recommendation for further research on reviewing and debriefing traumatic birth experiences.

For those who were expecting a complication, with either their health, the pregnancy, or the health of their infant, their trauma did not come from what they were prepared for. Many participants expressed their trauma was not associated with what they anticipated, with the remaining not anticipating any complications before their traumatic experience. Only one participant felt they had clear communication from their HCP, and most identified a lack of communication. Therefore, it is evident that clear and complete information needs to be provided by HCPs to reduce potential negative birthing experiences.

“We did feel like we had a good plan and we felt supported and then it was just like…we…were like left to the wolves…” (D)

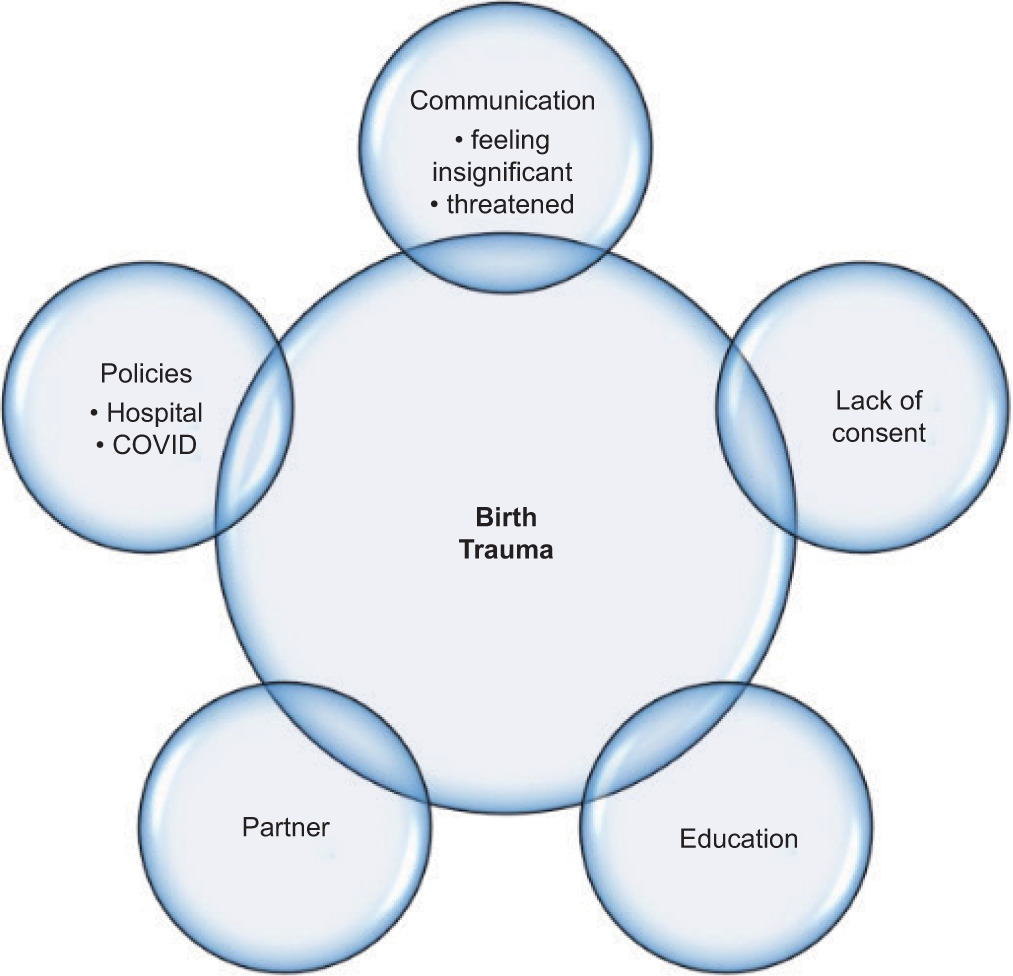

The five themes identified as contributors to the participants’ experience of trauma were education, communication, policies, partners, and lack of consent.

Data regarding the type of trauma was not tabulated due to the potentially identifying information that would have been associated with the incident. In addition, as PBT is subjective, and this research intended to identify the effect of perineal education on how the trauma is processed, the type or situation is not germane. Findings are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Findings.

| Participant identified issue | Total number of participants | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 15 | 16 | 94% |

| Prenatal Education needed | 11 | 16 | 69% |

| Trauma was not associated with what they had been prepared far | 10 | 16 | 63% |

| • Verbal education preferred | 8 | 16 | 50% |

| • Education through an App preferred | 1 | 16 | 6% |

| Communication | 13 | 16 | 81% |

| Lack af Communication from HCP | 10 | 16 | 63% |

| Understanding their story | 6 | 16 | 38% |

| Threatened | 5 | 16 | 31% |

| Difficulty remembering or no memory | 2 | 16 | 13% |

| Policies | 9 | 16 | 56% |

| Hospital policies | 6 | 16 | 38% |

| COVID related | 6 | 16 | 38% |

| Partner | 6 | 16 | 38% |

| Lack of consent | 5 | 16 | 31% |

Education

Almost all participants identified providing information on what to expect during pregnancy, labour, birth, and immediate postpartum as important for preparation for their birth experiences and would reduce the risk of PBT.

The trauma which was the focus of participants’ concerns was not associated with what they had been prepared for. The education participants received, such as information on health concerns regarding their child or themselves, assisted in providing a basis for handling the situation. Participants clearly identified unexpected events and lack of information as a significant contributing factor in their PBT. Practical information, such as the risks of induction and the risk of caesarean section, was frequently identified as being the topics participants felt would have been the most beneficial to learn more about from their HCP.

“I think if we do a better job at educating and informed consent, then we can trust that people are making the best decision for them. May not be the most comfortable decision for healthcare providers. That’s not their decision.” (G)

“I think I needed to know a lot more about induction ... I didn’t understand the consequences that come with that and the potential.” (I)

“I would have liked to know how real the risks would have been and if my weight played a part in those things, I would have liked them to have said so.” (M)

Participants shared that they felt well prepared for complications when anticipated, based on the education and information provided by their OBs, but they did not feel prepared for unexpected complications. More RM clients who either were a transfer of care before term or had a complication during the birth, reported they understood their birth story.

“Well, some women don’t like knowing though, but I found it really helpful that my midwife walked me through what to expect.” (O)

Participants who themselves were HCPs, stated their experiences during pregnancy, labour, and birth were influenced by their profession. They commented they were made to feel they knew or ought to know more about their situation. This led participants to feel unable to seek clarification. This was true for those working in specialities outside obstetrical care and those within. Participants, early in their careers when they gave birth, commented that if able to go back, they would have the confidence to interact with their HCP differently. Participants who are themselves also HCPs in obstetrics found it particularly challenging as their education led them to realize the situation was abnormal, and the intervention was not necessary, which contributed to the way they processed their traumatic experience.

“[What I] went through that pain . . . definitely being my body was violated without consent and without reason.” (N)

“No one explained anything to me and she wouldn’t really check for understanding either. Which is like super tough because I also didn’t want to look stupid.” (G)

“I felt very much was like not communicated to us and I do feel like that is because I they knew that I was a [profession redacted].” (D)

Communication

Most participants independently identified issues with communication, as a contributing factor to their trauma. Participants expressed that when HCPs appeared unable to deal with an urgent situation the panic displayed compounded the PBT whereas the emergency itself was not a contributing factor.

“Panicking like that’s scary to like someone in such a vulnerable situation like you being panicked and knowing it scares me.” (C)

Communication issues and interdisciplinary conflict have far-reaching effects on the family. The impact on parents was significant when different care teams discussed next steps and focused not on the care of their infant but on various priorities, such as research or further testing for genetics.

Sharing what they want HCPs to know:

“The biggest thing is just how much you can impact. By that, like their teams not communicating. Like there we had so many different teams involved and it was like they were almost fighting with each other about what was the most important care that [baby’s name] needed. And I think they didn’t understand how much that impacted [partner’s name] and I because then it was like all focus was on like their specifics.” (D)

“I did have a social worker in the hospital, but I feel like they were just making it worse because they were just telling me like the worst case is like and they didn’t get my hopes up. But like they didn’t give me any hope. They just said like they pretty much just kept telling me like, you need to pull the plug, you need to pull the plug… then I did get a second opinion from a different doctor… he was actually like, like hopeful, like, yeah, kids come out this. He might have like say, like, cerebral palsy or something. But like, they live their best life. They could give like the worst case and a good case like don’t just give everyone the negative, give them a positive outcome of it as well.” (B)

In situations with extremely poor prognosis, thorough communication with the family is beneficial. This assists in processing the situation and making appropriate decisions regarding care. Balancing discussions about the possibilities for their newborn; including the poor prognosis information and the possibility of hope even in extremely rare situations.

The lack of communication reflects the power dynamic between HCP and patient. When a routine next step seemed inappropriate, it was difficult for participants to speak up. Lack of communication from HCPs leads patients to feelings of insignificance. Participants stated they perceived their interactions with their HCP included feeling: judged, too fat, too young, uneducated, just a number, that their HCP did not care about them, they did not have a voice or a choice, and were unimportant. Communication in the moment is vital to feeling supported.

“Who am I to argue with doctors?” (M)

“I feel like . . . I just wasn’t seen as a human and ... I just want them to know that it wasn’t OK.” (M)

My “midwife really didn’t advocate for me at all.” (I)

Routine practices of an HCP should be shared with patients to ensure a common understanding. Reflecting on the lack of mutual understanding caused participants to wonder how different their experience would have been had they not undergone an unnecessary and painful intervention.

Several participants stated they felt they had been threatened. Scare tactics reported included “using the dead baby card”, refusing to discharge someone unless they agreed to the HCP’s recommendation, and being told “this is what I’m doing” with no alternatives and “you get an episiotomy, or we do a crash C-section” with no further communication from the HCP. When the ‘choice’ given was unrealistic such as, “You will have to push out your baby in one push or we are going to do…” it did not feel like a choice at all which led to their PBT.

The impact of HCPs is significant, with the most positive and powerful statements coming from participants reflecting on moments when their HCPs were present, supportive, understanding, patient, and caring. Reflecting on the patience of their HCP, one participant described the OB as such “a great space holder” (H), patient and encouraging, she recalled him encouraging her to put her foot on his leg for support, following her lead as to when she had the urge to push and delivering in a way which felt natural for her. Another recalled the support of her midwives and feeling “they were amazing”. She wondered how she could have “gone through all of that . . . trauma . . . without having a midwife” (O).

Policies

Participants were aware of the reality of hospital policies, particularly COVID-related policies. However, they encountered situations where the justification was unclear, or where the practices were inaccurately presented as hospital policy when they were HCP preference. Participants expressed the importance of understanding these policies in advance or as soon as possible. Information sharing and education throughout the perinatal period by HCPs would enhance their understanding and help them incorporate the policies into their anticipated experiences.

Hospital Policies

Participants expressed that hospital policies can be a source of trauma particularly when cited as the rationale for specific decisions. They felt that certain practices were used as excuses rather than genuine policies. For instance, being told they needed to be in a particular position, frequent cervical exams, not being permitted to increase oxytocin levels naturally, signs encouraging Kangaroo Care but reality being restrictive, and masking policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Even the recommendations for further interventions were seen as excuses to adhere to provider preference and identified as sources of trauma:

“They don’t care about my life after that moment. They don’t care . . . they don’t want me to take up space.” (M)

COVID-19 Hospital Policies

The impact of COVID-19 hospital policies added another layer to the impact of policies on the participants’ PBT experiences. Almost half of participants expressed that the COVID hospital policies harmed their experience while one participant felt it beneficial as it provided time with their partner and space from extended family, without the need for difficult conversations.

“I didn’t want everyone there, and I really liked the privacy that it gave, and I didn’t have to have a . . . hard conversation because the hospital just did that for me. I wanted that time to be me and my baby and my husband.” (O)

Most participants described their experience concerning COVID restrictions for themselves and their partners, with terms such as alone, horrible, held hostage, had to choose one person, and relating the experience of labouring in a mask to a prisoner labouring in handcuffs. Others commented on the dichotomy of COVID policies which restricted the number of people patients could have as support in their room but when it came to hospital staff there were “about . . . 10 people in the room” (I). Birth trauma themes are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Themes.

Partner

The impact of the birth experience on the partners of birthing people was a principal factor in PBT for several of the participants. Participants expressed that the impact on their partner of a negative birth experience caused adverse psychological effects on themselves. Comments regarding their partner’s experience and how it continues to affect them included: when their partner asked questions and they were not given answers, still (even years later) not having processed the experience of the birth, feeling that they (the partner) missed an important aspect of their child’s birth and wishing they could have been a bigger part of the experience, feeling that no one acknowledged them or cared about their emotional or physical wellbeing and feeling unbearably traumatized by the birth experience. The emotions associated with these experiences can leave partners with feelings of anger and abandonment.

“He was not impressed in any of the experiences to the point of tears ... he says ... if anything were to happen to you, that’s still my child.” (M)

Lack of Consent

Several participants experienced issues such as interventions being performed without prior consent, HCPs failing to follow pre-planned hospital-created care plan because they forgot, and a lack of sufficient information to make informed decisions. The lack of consent was directly linked to their PBT and for some identified as being linked to feeling as though they were assaulted.

“I just curl up in a ball and ... it felt like I was sexually abused.” (N)

“Sorry, we forgot about that.” (D)

“We had like this great plan and then it was just ... all completely out the window.” (D)

“That it was so fast that I couldn’t understand what was happening until it was done.” (H)

One participant spoke about the frequent cervical exams, telling them to stop and not stopping, telling her to calm down or they were going to put her to sleep (with a general anesthesia). She explained that “they don’t care about me . . . I’ve been in their bed for too long and that’s all they care about.” (M)

The College of Midwives of Ontario includes the concepts of voluntary and informed consent, the need to provide informed choice in all aspects of care, and the concepts of “allowing clients adequate time for decision making” and “supporting clients’ right to accept or refuse treatment.”36 The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario likewise guides consent to treatment, including informed, voluntary, expressed, or implied concepts.37 Yet it is clear in the comments from participants they did not feel they had given voluntary informed consent to treatment or interventions. It is outside this paper’s scope to determine the HCP’s intention in those situations. However, even when examining these situations with the lens that care is being provided in an adept, attentive manner, the lack of consent participants reported needs to be addressed. An absence of articulation for their disapproval of a situation does not equal consent. It is up to the HCP to obtain clear and informed consent.

In situations where a care plan is made, which provides patients with a sense of control and increased knowledge then forgotten or ignored, adds to the trauma experience. Participants commented that lack of consent felt like a violation of their body without consent or reason, contributing to a lack of understanding of the situation, and included vaginal exams without consent.

DISCUSSION

Overall, participants found the information and education provided by their HCP, prenatally, to be of significant value and instrumental in mitigating the trauma experience of birthing people. This finding is crucial as it highlights an opportunity for HCPs to directly and markedly reduce the PBT experienced by their patients. Given that most births in North America happen in hospitals and involve nurses at some point in their care, it has been argued that nurses’ are in an ideal position is to empower women through their birth experience.38 It should be argued that all HCPs are in the ideal position to fulfill this role, and it is the responsibility of HCPs to ensure the principle of nonmaleficence is followed. Whether the harm is of a physical or emotional nature, it is still the HCP’s role to ensure it does not occur.

It has been recognized that HCPs can cause or negate trauma as a result of their actions during a birthing person’s experience.38 Education about and critical reflection on traumatic childbirth should also be included in the curricula of education programs of the relevant healthcare professionals and lifelong learning of maternity care professionals, to ensure they are aware of the factors that contribute to optimal childbirth, including shared decision making and personalized care.39

Considering the critical role of perinatal education as highlighted by participants in preparing them for anticipated complications, and their identification of insufficient perinatal education as a source of their PBT, it is essential that comprehensive education be provided throughout the pregnancy and birthing journey. Providing participants with further education on signs and symptoms based on their history could identify concerns before significant issues arise. The typical “How are you feeling?” Inquiry should be further described with elucidative questions such as: are you having pain? Where is the location of pain? Describe the pain, any headache? Describe your headache. Patients will then be able to respond accurately and provide the information needed to HCPs to make appropriate and timely diagnoses avoiding detrimental effects of worsening conditions.

The impact of information provided or withheld is significant. Participants expressed a strong desire for clear communication at the time of a critical incident to help reduce their trauma experience. Including information on more common obstetrical emergencies such as unplanned caesarean sections, hospital policies, and HCP preferences. It also fosters open dialogue regarding patient preferences before critical situations occur. This approach would ensure better communication and clarify expectations.

As HCPs, the single most important thing we can do to support our patients is to communicate – prenatally and in the moment during the intrapartum period. Ensuring options are provided along with the risks and benefits of each are discussed with the birthing person and their chosen support person. Receiving consent and halting interventions when patients decline them. Be clear if an action or recommendation is a professional recommendation or a hospital policy. Collaborating with patients to identify and alter hospital policies that do not meet their needs.

In accordance, with gender inclusivity as principled by midwives in Ontario and throughout Canada, this paper endeavours to use gender-inclusive language.40,41

LIMITATIONS

Representation through population matching was not possible due to the number of participants. It therefore did not specifically include balanced experiences of Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) and Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (2SLGBTQ+) childbearing individuals. One participant identified themselves as Black and Indigenous, and another identified themselves as Muslim. The results cannot be extrapolated beyond the research participants. Research into the birthing experiences of trans and non-binary individuals is emerging and needed, as it is believed they face vulnerability that cis women do not.42,43

The recruitment criteria for participants including having given birth in the previous 5 years, created overlap with the COVID-19 pandemic and the significant impact on the healthcare system worldwide. Restrictions from the pandemic and the implications for labour/birth/postpartum experiences and on the way that traumatic events are processed cannot be excluded.

The tertiary centre was selected to eliminate the impact seen in level 1 and 2 hospitals when there is a need for a higher level of care. It is reasonable that transportation and separation from their infant could compound any trauma felt.

Unfortunately, the recruitment of patients of FMOBs was unsuccessful with no participants recruited. Therefore, the aim of this study to identify if the information provided to patients varies between OB, FMOB, and RMs was not clearly achieved due to the lack of FMOB patients. Upon reflection, reasons for this lack of participation could include the way patients identify their physician as either an OB or Doctor; that HCPs may not have defined PBT in the same way that was intended for this paper, and the recruitment was not shared with perspective participants; utilization of social media and snowball recruitment would have excluded those who did not see the poster or who were not aware of the research project. Missing the voices of patients of FMOBs is a serious shortfall of this research. The ongoing relationship between FMOB and their patients may positively impact patients’ ability to process PBT experiences.

CONCLUSIONS

Through guidance and information provided by the participants, the themes identified contribute to the body of knowledge by outlining an early framework that can be applied in the education of HCPs to identify approaches to reduce the negative impact of PBT. The themes identified indicate prenatal/perinatal education and communication would reduce the impact of PBT. Implementing clinical practice in which education on potential birth emergencies is routinely discussed will provide the opportunity to learn, anticipate, and prepare for unexpected events. As institutions revise and develop new policies, evaluating the impact of these structures on PBT will provide an additional lens through which policies can be reviewed. Recognizing the importance of partner relationships, or for single patients, the absence of a relationship is vital to acknowledgment as a family unit. Despite the undisputed autonomy of the birthing person, their partner often is aware of their preferences and should be included in decision-making conversations. Consideration of the partner’s involvement and emotional state would improve the experience of birthing people. Ensuring full consent before and during interventions for routine and urgent care situations is crucial for providing care that is patient-focused, trauma-informed, and meets ethical considerations including nonmaleficence.

Communication is vital to reducing the experience of PBT as seen in this research. When participants were prepared for a possible critical outcome, they did not experience trauma related to it. This has an impact, and clear communication without persuasion, coercion, or manipulation is essential for patients to feel respected and heard. Consent needs to be obtained after providing complete information, and time must be taken to consider options. Healthcare providers need to respect that patients are not making decisions in isolation. Ensuring their support person is included in the conversation and understands the situation will positively impact the experience of birthing people. Finally, HCPs need to use hospital policies appropriately, identify when policies are not meeting their patients’ needs, implement patient input into policies as much as possible, or be transparent about how patients can decline following a hospital policy.

Recommendations for further research include building upon existing knowledge and expanding investigations in several areas: the impact of prenatal and perinatal education by HCPs on marginalized communities; the effect of PBT for those birthing in Level 1 and Level 2 hospitals who require higher level care; the influence of COVID related public health and hospital policies on PBT; the experiences of partners of birthing people during traumatic births and its effects on the birthing person; and the experiences of birthing people who are themselves HCPs, particularly the impact of how interactions with their care providers impact PBT.