STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

| Problem | What is known | What this paper adds |

|---|---|---|

| A shortage of midwives across Canada brings to our attention the need to focus on their attrition from the profession. | Midwives’ experiences of poor workplace mental health influence their attrition from the profession. | This study provides evidence of the importance of collegial support of midwives’ mental health in general, of their return to work and ultimately, retention in the profession. Financial coverage of leaves of absence were a notable facilitator. |

INTRODUCTION

Problem

A global shortage of midwives brings to our attention the need to focus on the factors affecting the attrition of midwives from professional practice. There is limited international and Canadian evidence of the factors contributing to attrition from midwifery due specifically to mental health issues.1,2 Indeed, there is a need to come to a better understanding of different factors that impact the mental health experiences of midwives and midwifery students in Canada and, in turn, how they respond to these experiences by contemplating or taking a leave of absence and returning to work or exiting from the profession.

Attrition from Midwifery and Retention of Midwives

Midwives play an important role in providing high-quality maternity care and rapid and sustained maternal and newborn mortality reductions.3 Still, in Canada and internationally, this essential health workforce is a shortage.4 Indeed, some data demonstrate that, along with nurses, midwives represent over 50% of the existing health worker shortages globally.5 The density of midwives in Canada (4/1000 live births) is notably lower than other Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries such as Australia (68) and the UK (43).6

A high number of midwives leaving a profession contributes greatly to the shortage trend. One international report has revealed estimates of voluntary attrition from the wider midwifery workforce ranged from 1% to 22%.4 Not surprisingly, the attrition rates became especially high during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, in the UK in 2021, the highest number of midwives in the past twenty years, approximately 300, left the profession within two months.7 In such a context, it becomes crucial to fully understand all the factors that may lead to attrition to reverse it and retain midwives in healthcare systems.

Evidence shows that the reasons for leaving midwifery practice represent a mix of work-related, organizational, personal, and system-level factors, including heavy job demands, unmanageable workloads, concerns about delivering safe care, dissatisfaction with the organization of midwifery care, lack of social and professional resources, conflict with colleagues, dissatisfaction with managers, feeling undervalued at work or by government, challenges with finding work-life balance, and health system fragmentation.2,7–10 High attrition contributing to midwifery workforce shortages has serious consequences, ultimately affecting the burnout of remaining midwives, the safety of practice, and care of mothers and newborns. Some evidence shows that shortage is directly related to poor provision of quality care and maternal and newborn deaths.4,11 Globally, the acute shortage of midwives is taking a terrible toll in the form of preventable deaths. An analysis showed that fully investing in midwife-delivered care by 2035 could help avert 67% of maternal deaths, 64% of newborn deaths and 65% of stillbirths.4

More promising is research on factors that facilitate or encourage the retention of midwives, including: satisfactory salary, ‘met preference’ for hours of work and on-call weeks, having autonomy in their work, positive relationships with clients, partners, colleagues, and family, feeling a great sense of accomplishment through their work, and feeling passionate about midwifery.2,12,13 Considering the importance of a healthy midwifery workforce to infant and maternal health and a robust healthcare system, evidence-based targeted research identifying professional retention strategies is warranted to inform occupational policies and workplace programs.

The Role of Mental Health in Midwifery Attrition

Midwives’ mental health

As it is the case with other health workers, midwives experience challenging workplace mental health concerns. The literature shows that the most prevalent mental health issues faced by midwives are psychological distress/stress,10,14 burnout,15,16 anxiety,17 secondary traumatic stress,18 and posttraumatic stress disorder.19,20

Stress and burnout that midwives face in their jobs was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic.21,22 Findings from a qualitative study in British Columbia found midwives experienced a lack of support and recognition during the COVID-19 pandemic. Midwives’ workloads increased significantly during the pandemic, and they expressed that they did not feel acknowledged as ‘frontline workers.’22

Many studies suggest that work-related and organizational factors, including long hours, heavy workloads, on-call work, lack of resources/staff, the introduction of new technologies in healthcare, job security, emotion work, dysfunctional working cultures, workplace bullying, low morale, lack of career progression, and inadequate remuneration models predict psychological distress/stress, anxiety and burnout in midwives.14,20,23–25 While non-work/organizational factors are less often explored in the literature, some evidence identifies certain family (e.g., having children) and personal characteristics (e.g., being young) as being associated with a higher prevalence of burnout among midwives.25,26

Mental health concerns and midwifery attrition

Although scarce, some evidence shows that mental health-related concerns like burnout, which stem from challenging working conditions, may lead to midwives’ decision to leave midwifery temporarily or permanently, even during professional training.1,25,27 For instance, a Canadian pilot study examining leaves of absence and return to work among midwives who experience mental health issues pointed to challenging working conditions and critical incidents (unfavorable outcomes) that pose mental health challenges impacting midwives’ working ability and leading to leaves of absence or attrition.1

Midwives’ Return to Work

We know very little about the return to work of midwives after a leave for mental health reasons. The literature suggests that organizational support is an important factor in facilitating return to work for midwives with mental health concerns. In one paper on mental health sickness absence among nurses and midwives, it was noted:

“Health organizations in the United Kingdom have reported significantly reduced staff absenteeism with modest investment in a specialist nurse role focused on return to work of absent nurses, with processes involving periodic phone calls to absent nurses and with employment of specialist mental health nurses, manager training, flexible working programs, psychological therapies for staff and access to specialist allied health and education.”28

Some key barriers to midwives’ return to work after taking a leave for mental health reasons is the occupational services’ lack of expertise to deal effectively with mental health concerns experienced by healthcare professionals and managers’ refusal of guidance provided by occupational services.29

Overall, the issue of the mental health experiences of midwives and midwifery students and their role in the decision to leave temporarily or permanently remains largely unexplored in Canada as it is elsewhere. In particular, we need to know more about factors impacting the mental health experiences of midwives and midwifery students, leaves of absence or attrition, and their process of return to work given the variability in work and organizational structures across the country.

Methods

We draw upon data gathered from midwives and midwifery students (midwifery case study) who participated in a larger mixed method national study that focused on professional workers (academia, accounting, dentistry, medicine, teaching and nursing case studies) across Canada who have experienced mental health and return-to-work issues for either personal, familial or work-related reasons. One other published manuscript has been produced with this data set, and focused on gender and leadership as it relates to mental health leaves of absence and return to work.30 We sought to understand what aspects of midwifery that work shape the mental health of midwives. We collected two forms of primary data: surveys of 202 midwives, midwifery students, and retired midwives, and interviews with 44 workers (33 midwives, 11 students).

Surveys

Data were drawn from a bilingual, crowdsourced online survey targeting midwives across Canada. The survey was available between the end of November 2020 and May 2021. The survey included several questions focusing on the mental health, leaves of absence, and return to work pathways, as well as questions about mental health, distress, presenteeism, and burnout before and during the pandemic. There were 202 midwifery participants who completed the survey.

Of the 202 participants, 188 (94%) identified as women, 7 (3%) identified as non-binary/gender fluid, and 6 (3%) preferred to self-describe. Concerning other demographic factors, 8% of participants identified as racialized, 6% Indigenous, 6% living with a disability, and 31% said they were the sole income earner in their household. Most participants lived in Ontario (n=111), with a substantial portion from British Columbia (n=30), Alberta (n=12) and Québec (n=11). Most were independent contractors (i.e., fee for course of care). Descriptive analyses of the survey data included frequency cross-tabulations with tests of significance undertaken at a p<0.05 criteria. The survey did not require all questions to be answered, so the sum of responses was not always equal to 202. Our data suppression rules also prevented the export of cell sizes less than or equal to 5. We inquired with those who participated in the survey if they would be willing to be interviewed. If they agreed, we engaged them for an interview.

Interviews

In-depth interviews were conducted in English or French via Zoom by several of the authors in groups of two between January and July 2021. A semi-structured interview guide was designed under the authors’ leadership in consultation with our study partners (i.e., professional associations, regulatory bodies, etc.). Before each interview, the participant signed an informed consent form. Interviews were audio-recorded, and notes were completed by the research team’s students and co-investigators.

Interview participants resided in seven different jurisdictions nationwide (47% in Ontario, and the remaining from Manitoba, Alberta, BC, Québec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia). Of the 44 participants interviewed, 95% identified as cis woman, and 5% as non-binary or gender non-conforming. Participants worked as salaried employees (24%) or independent contractors/fee for course of care (22%).

The qualitative analysis was conducted using NVIVO software. Interview data were transcribed, coded, and thematically organized based on predefined themes of interest that were reflected in both our interview guide and survey questions: mental health issues, causes, and interventions; workplace mental health promotion policies and programs; presenteeism, working while sick and absenteeism, missing work for physical or psychological reasons; return to work factors, policies, and programs; and gendered experiences. This baseline coding scheme was generated deductively and applied to the midwifery case study by the project team. It was subsequently built upon to reflect the unique aspects of the midwifery data and adapted as novel themes emerged.

Results-Survey and Interview Findings

Our survey results gave us insight into the pathways midwives took when experiencing mental health challenges. Our interviews gave further insight into these pathways regarding work context, content, and organizational factors. We have integrated our findings from both data sources in the following sections. To understand mental health and the impact on work, we asked questions that focused on presenteeism, impact on work function/quality, ability to take a leave, intent to leave, support and difficulty to leave, and support for return to work and accommodations.

The Pathway from Mental Health to Leaves of Absence and Return to Work

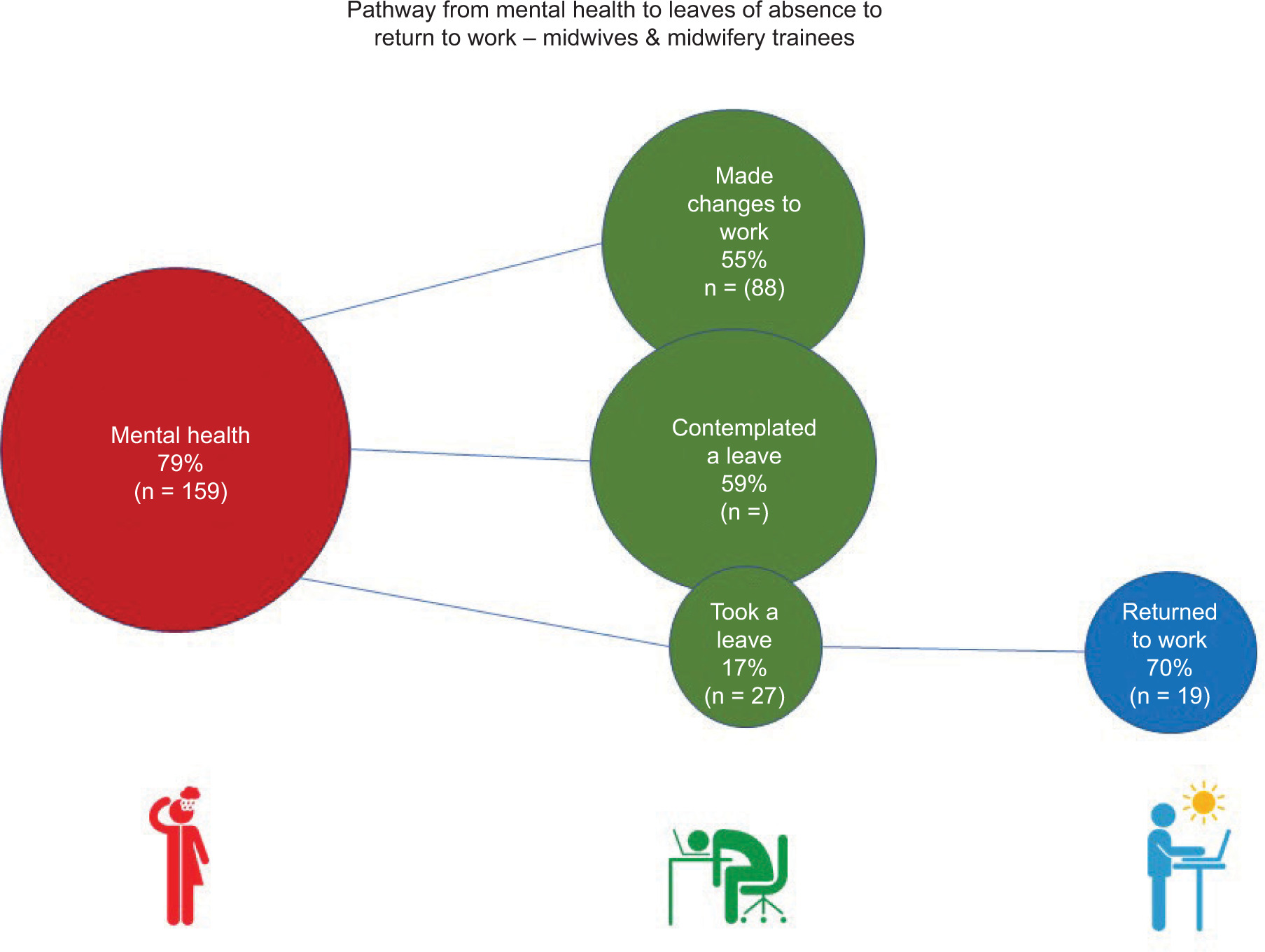

Our survey shed light on the percentage of midwives reporting mental health issues, and the pathway they took when suffering from a mental health issue. A summary of these findings is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mental health, leave of absence and return to work.

Impacts on Mental Health: Individual, Work, Professional, and Organizational Factors

At the individual level, factors impacting mental health concerns among midwives included personal and familial concerns. One midwife stated:

And the real tipping point was when a colleague asked me if I would be available to work Christmas, be on call for Christmas Day. And being the first year in this new family setting where I’m now looking at spending every other Christmas by myself. That was too much to ask, it was the straw that broke the camel’s back. (MDW-WI-28)

In addition, at an individual level, midwives expressed a reduced physical capacity related to recovery from long shifts. One participant stated a focus on exercise helped with coping:

“… what I did for myself was exercise more, and just try to focus on sleep and exercise.” (MDW-WI-44)

Work-related factors included critical events or incidents, emotional and ethical challenges, and working with complex or vulnerable populations. Work context factors related to the demands of on-call work, inter- and intraprofessional dynamics, personal autonomy and control, integration into hospitals, and various models of care. Aspects of the model of care (how midwives work) such as continuity of care (midwifery care throughout prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum) was noted to have an impact on mental health of midwives:

“… some things, I just don’t think there’s a solution to. I think the real challenge of midwifery is that because one of the wonderful things we offer is the continuity to our clients is that ... they know a small number of midwives. And those are the people who will be with them while they’re in labour. I think that’s a very, very important part of what we do. But the... way that manifests itself as a job structure is then you have all this on-call time to be able to offer that continuity.... someone has to be on call.... one of the frustrations and stressors of the job is that you actually know there’s no solution.” (MDW-WI-13)

At the professional and organizational level, midwives described the challenges of managing bureaucracy when seeking support or accommodations, interprofessional dynamics (including bullying and harassment) and the differing professional beliefs of what it means to be a “good” midwife (e.g., tensions between patients’ needs vs. midwives’ needs, continuity of care vs. shared care models) which tend to be connected to the notion of work-life balance. One midwife commented:

“...there’s also a sense of this in the midwifery community, …. ‘Oh, you don’t do full scope (antepartum, intrapartum, post-partum).’ So, I’m a lesser midwife because of that.” (MDW-WI-05)

Another midwife working within an employment model, shared, regarding the important role of management:

“…there’s only one person, the manager, that one person is dictating how things work, the schedule, when you get to be on call if you get to have a vacation … It’s been a very difficult 10 years of having a lot of midwives leave…” (MDW-WI-23)

As shown next, our survey results support our qualitative findings related to midwives perceived mental health support from management/supervisors (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Midwives perceived mental health support from supervisors.

Impacts on Mental Health: Midwives’ Perceived Supports

Data from our interviews revealed positive workplace cultures and supportive colleagues were cited as contributors of positive mental health. Some midwives had colleagues who encouraged them to care for their mental health:

“… I just sat there crying in a meeting, like the tears were just falling on my face. And my dear partner…said, ‘give me your pager’…She took my pager from me. She said, ‘you go home; you take care of what you need to do…you need time off’…And so they were so supportive of that. She actually took my pager away from me…I was able to take some time…they were so supportive, my practice.” (MDW-WI-22)

Others highlighted the role of supportive managers, for example:

“I decided to go sit down with my manager, before my clinic day started and explained to her all the things that were going on, and she essentially walked me out of the building, she said, “You need to go home and think about what you need”, and told me that my clinic day would be taken care of. MDW-WI-28)

At an organizational level of work, midwives mentioned some existing resources were helpful and available to them.

“I have used the call line years ago…A teammate had a pretty significant mental health break…I called them the next morning because I’ve actually took them into emerge and, that was exceptional support.” (MDW-WI-04)

Another midwife highlighted her Midwifery Association as an important resource.

“…We have a Member Assistance Program, which is run by our association…[which] offers employee assistance program…The majority of the reasons that people call is for access to counseling, there’s…financial planning and legal and other stuff that’s available, …We do have a benefit program also run through our association…it does have Counseling Psychology, like it has resources through there if people exhaust what’s available through the Member Assistance Program…and disability benefits…” (MDW-WI-06)

Deciding to Take a Leave of Absence: Midwives’ Perceived Barriers & Facilitators

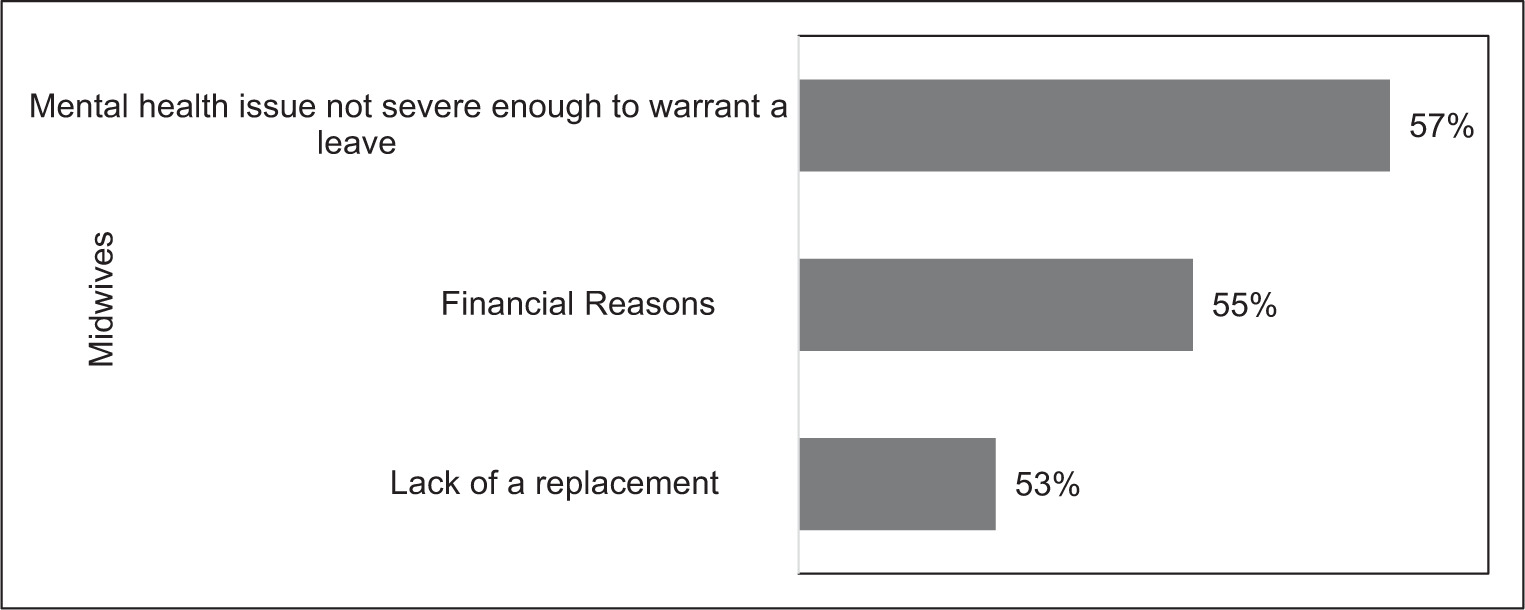

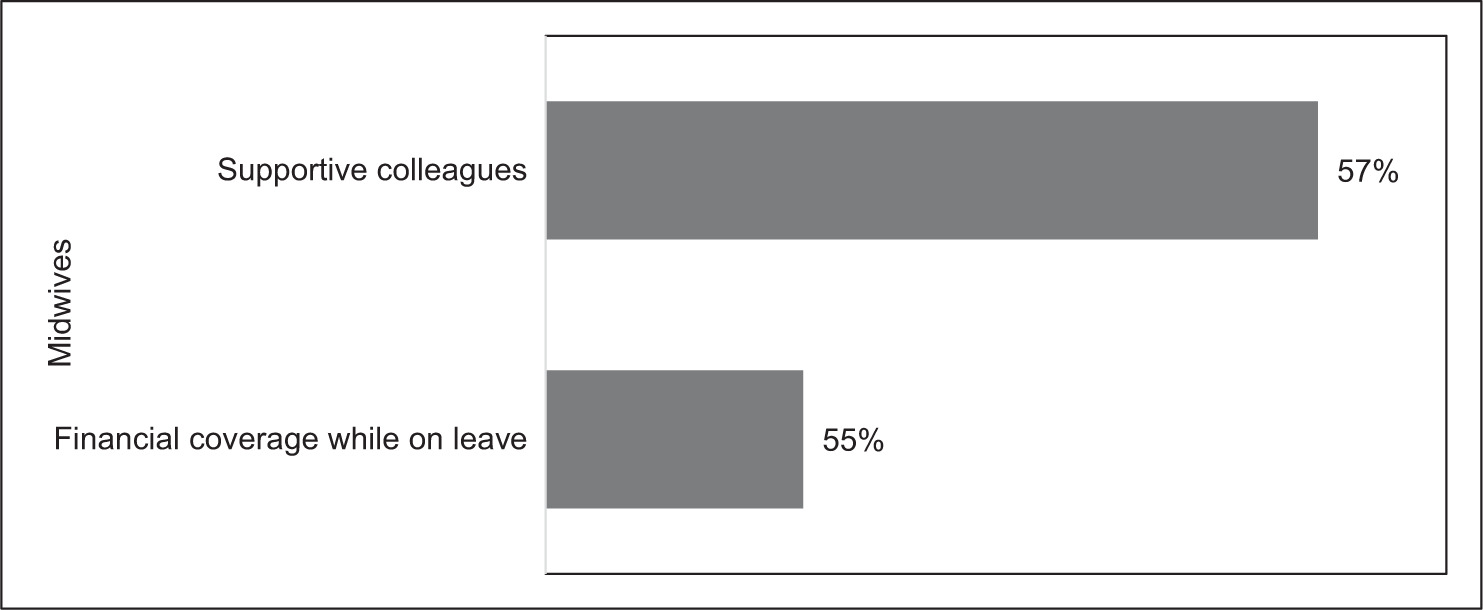

According to our survey results, the top reason for not taking a leave was the mental health condition was not deemed severe enough (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Barriers to taking a mental health leave.

The main reason midwives felt they could take a leave of absence was attributed to supportive colleagues (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Top two facilitators to take a leave of absence.

During the interviews, midwives discussed how they considered, but did not take a leave of absence, citing the main barriers as lack of access to locums, lack of economic viability, guilt towards colleagues, and lack of support at the organizational or institutional level. Some midwives also described that they would have taken a leave of absence, but instead utilized lieu time and vacation days, taking education leaves, relocated to a different practice, or left the profession entirely. One midwife shared the burden felt when a colleague took a leave of absence:

“One of my girlfriends reached a breaking point (taking on extra clients from a midwife on leave). It’s not our decision to hire someone else. We have to apply to the government… I don’t want to deal with the politics. I think I might be done with midwifery, or at least working in this manner.” (MDW-WI-02)

Another midwife commented on the impact a leave of absence has on the team and how this was an important consideration in her decision-making:

“[A midwife on our team] wanted a leave of absence... but it would severely impact the team for months…, but the request doesn’t come to us, that goes to HR. HR denied it. And then she went to the team and the team gave her a month off, and they worked harder for her to do that.” (MDW-WI-0)

This midwife commented on the financial implications of a leave of absence:

“.. [leave of absence] is an unpaid leave. So, this was not an easy decision to make and is having repercussions for us financially. If it was something I could have afforded to do, we probably would have, I probably should have and would have taken a leave sooner.” (MSD-WI-23)

Participants stated the lack of economic viability and student debt as contributing to presenteeism, in addition to a workplace culture that expects them to “suck it up” and work when they are sick. Participants also described experiencing critical incidents and the effects of burnout, such as compassion fatigue and apathy before seeking a leave of absence. They also commented on the lack of support from practice groups due to the current state of the workforce:

“…You can take a day off, but you’re also making it up in other ways, most of the week anyway. So yeah…” (MDW-WI-19)

And,

“… there’s not really much support from the practice…I would say that my group is not healthy, emotionally or physically, that a lot of the members have chronic issues...” (MDW-WI-18)

According to participants, burnout was a common reason for taking a leave of absence. Participants noted an inflexibility in their model of practice and a lack of alternative professional opportunities, leaving them with no other option but to take a leave:

I wasn’t offered, no one offered me support. Like, at work people were, I told my boss, when this was first going on. I asked, I said, I might need a leave of absence because I was a real mess. And she said, “Okay, well try to work. Sometimes it’s good to work. But if you need to take a leave… that’s something that we can consider…do what you need to do, because you can’t come to work and just cry.” (MDW-WI-42)

In terms of facilitators taking a leave of absence, one participant commented on the importance of a different employment model to ensure a leave of absence could be taken regardless of the burden it may bring to their practice:

“I think you’ll probably still feel the same amount of guilt towards your partners [when taking a leave]. But [as an employee] you have a legal framework in place through your collective agreement with your union that allows you to be able to leave.” (MDW-WI-20)

The students in the Midwifery Education Programs (MEPs) across the country commented on how stress from the educational program impacted their mental health. Some said the lack of mental health supports was linked to dropping out of the program before completion. Students also discussed a lack of support from faculty when expressing concerns related to discrimination and feeling unsafe reporting such concerns due to an all-white faculty, situated in a “suck-it-up” culture which had an impact on mental health.

One trainee commented on their experience as a midwife student:

“…I spend like most time at home and I’m just like doing bad and I didn’t talk to anybody because I feel that it’s not valid to tell professor I couldn’t sleep for like…I slept only one night because of panic attacks. I don’t want to reveal too much because…I don’t feel that I can share with them. And be judged that maybe I’m like, over exaggerating...” (MDW-WI-08)

Students in MEPs identified some of the resources available to them at their universities:

“…the only thing that I was able to do, it was like ask for counseling sessions at my university, and I talk with counselor at university…” (MDW-WI-08)

Pathways to Return to Work: Midwives’ Perceived Barriers & Facilitators

A gradual return to work was the most prevalent enabler described by midwives that facilitated successful and sustained returns from leave. This may be administrative, managerial, or other non-clinical work, taking time to refresh clinical skills, working as a backup for colleagues, taking on shorter or no on-call schedules, part-time caseloads or only very low-risk patients.

The very few barriers to return to work cited by midwives include a lack of accommodations or flexibility in their model of care, such as an absence of formal policies or practice protocols, resulting in immediate return to full caseload or midwives leaving the practice.

Intention to Quit

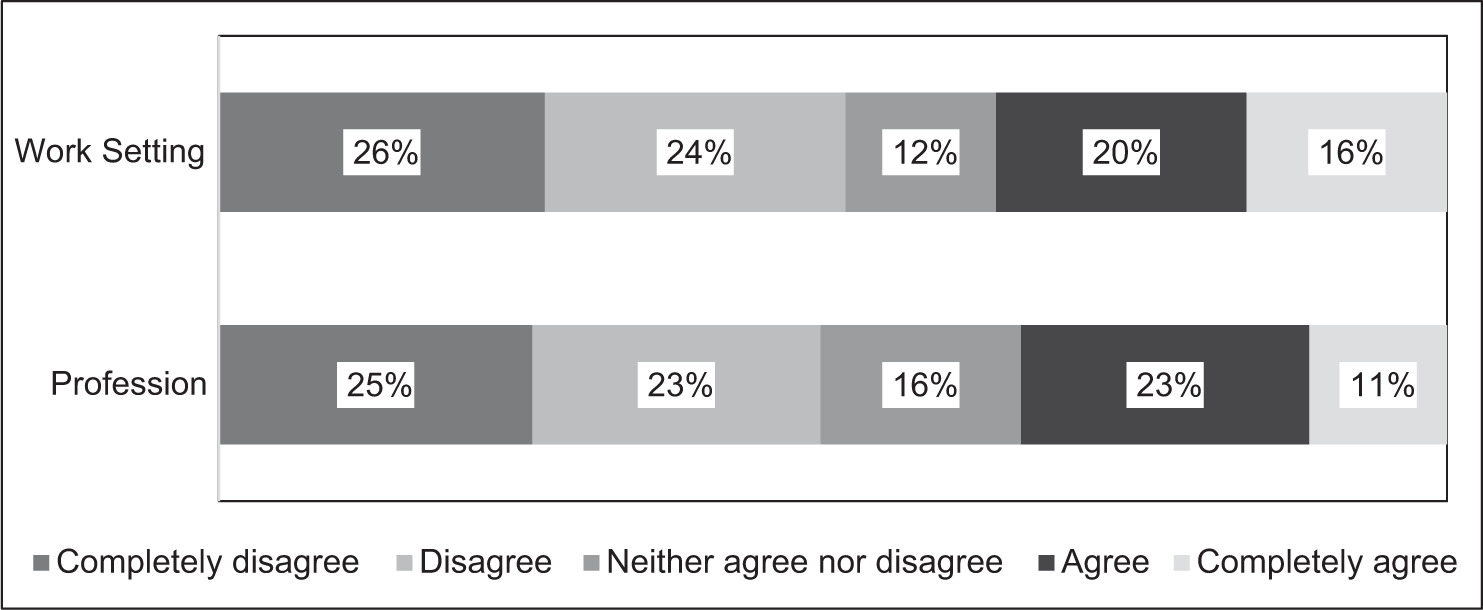

Another interesting and important survey finding was regarding midwives’ ‘intention to quit’, where 50% of participants agreed or completely agreed with statements that described their intention to leave their current work setting (organization), while 48% agreed or completely agreed with statements which described their intention to leave the profession. These stark statistics reflect quitting work or leaving the profession as a potential solution to workplace or professional burnout. (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Intention to Quit Current Work Setting (organization) and Profession.

DISCUSSION

This paper aims to understand how the nature and context of midwifery work shapes the mental health of midwives and midwifery students. Currently, burnout of midwives across Canada is at an all-time high, while the need for midwifery services continues to grow. Our study results demonstrate that the poor mental health reported by our participants is multi-layered, with most factors beyond their control. This aligns with results from a recent Canadian study regarding burnout and the midwifery profession.31

The current study expands on findings from our pilot study related to factors that impact the mental health of midwives1 and revealed many factors that have impacted midwives’ mental health related to the nature of their work. From individual to organizational levels, we understood that long shifts, work-life balance, midwives’ model of care, and the burden of working in a group practice could impact midwives’ mental health. Midwifery students also felt stress and burnout from the nature of the work in the profession. Additionally, leaves of absence were not easy to initiate due to factors such as burdening the team or stigma of taking a leave of absence. Returning to work proved similarly challenging due to system-level issues such as re-registration, lack of back-to-work accommodations, or inflexibility in the midwifery model of care. Despite these challenges, participants also identified enablers that supported their mental health, including having supportive colleagues and formal system-level frameworks in place that support taking a leave of absence.

Our findings also show mental health challenges among midwives in Canada is worsened by the limited employment models available across the country. In the early days of regulation of midwifery (mid-1990s), fee for course of care midwifery was implemented to ensure continuity of care for clients and autonomy for midwives, who faced competition and sometimes ridicule from family doctors and obstetrical nurses in hospital settings.16,32–35 Twenty-five years later, while many gains have been made for midwives - demonstrated by their increasing numbers across the country, growth in independent midwifery training programs, and personal satisfaction with the job related to the nature of the relational work with birthing people - burnout for midwives is pervasive.2,25,31,36

In response to the mental health challenges reported by midwives in Canada, regulatory bodies across the country have started implementing more diversity in the midwifery model of care via alternate practice models.37,38 For instance, a pilot project is currently underway that integrates two registered, salaried midwives into a comprehensive primary care youth clinic and evaluates the workforce mental health benefits and challenges associated with this alternate model of midwifery practice.39 Two recent articles draw attention to maternity care organizations as having a responsibility to ensure the wellbeing and health of their midwives.40,41 Doherty & O’Brien engaged midwives as active participants who helped to inform strategies for addressing burnout at an organizational level. These findings support this study’s results related to enablers that help to reduce midwives’ burnout, such as debriefing adverse life and professional events, improved working relationships with colleagues, having flexible work models, supporting organizations to provide viable resources, and overall, a commitment from the health care organization to prevent burnout.40

At the national level, the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences has produced reports on the state of the health workforce that support our findings related to intention to leave, moral distress, and burnout.42 Nationally, there is recognition that midwifery burnout in the workforce is impacting sustainability of the profession. The State of the Worlds Midwifery report (2021) acknowledges midwives as significant responders during the pandemic. Despite being overworked and under-recognized, governments continue not to invest in these services.43

Clinical implications of this study directly relate to access to reproductive health care. Midwives provide a comprehensive approach to care. They provide choice and continuity. Midwifery care is considered essential in some provinces, such as British Columbia, and worldwide. When the system does not support the workforce to thrive, access to reproductive health is jeopardized.

LIMITATIONS

This study yielded robust data that helped us understand factors that impacted midwives’ mental health, return to work, and leaves of absence. Still, there were some limitations to our study. In particular, the crowdsourced nature of the survey recruitment, which was conducted online, diminishes the generalizability of the survey findings. Also, mental health experiences were self-perceived by the survey participants. Moreover, we were not able to fully understand the impact of the model of employment on the mental health of midwives, although one could draw some conclusions with the evidence. We were also unable to understand how newer alternate models of care support work-life balance. Thus, future research could focus on the employment model’s impact on midwives’ mental health experiences and work-life balance.

Conclusion

Our results identify key individual, organizational, and professional factors that significantly impact the mental health of midwifery professionals. It stands to reason that the role of midwives in promoting physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual wellbeing is an immeasurable contribution to lifelong health and wellness. The mental health of midwives as clinicians and health care providers has far-reaching impacts beyond their own professional realm – shaping one’s experience of the health care system while still in utero. Supporting a healthy workforce is critical as we recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and face unprecedented shortages of healthcare providers across Canada. Ensuring that midwives receive the occupational supports they need to provide quality care to their clients, will maintain as Anderson says “madjimadzuin, the “moving life” or Human Milky Way.”44